Injected with saltwater?Oh, yes. It’s called “plumping”. The amount of saltwater injected in raw chicken meat can be anywhere from 10 to 30 per cent, depending on where you are in the world. Of course you won’t see that in the label. But understand that because the chicken is weighed after the saltwater has been injected the numbers you see on the label refer to the chicken’s padded weight.

So, whether you’re buying a while chicken or cut-up chicken, unless you’re buying from a poultry farmer directly, your chicken has saltwater.

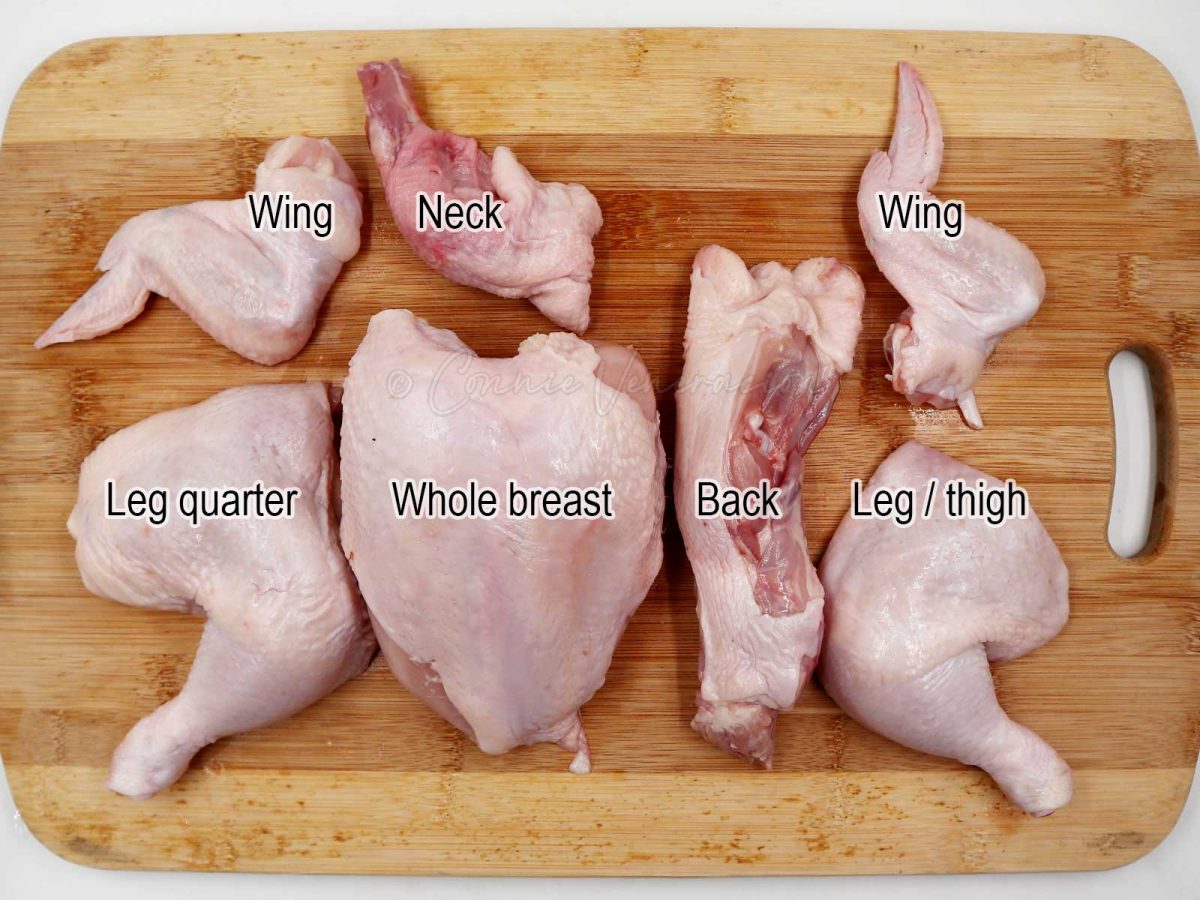

Commercial chicken cuts

It’s easy to buy a tray of chicken thighs, wings or breasts but if you’re serious about cooking chicken, you should at least know how to cut a whole chicken. If you buy your chicken whole, these are the portions you can get from it.

To cut up a whole chicken, always locate the joints and cut there. When you have the chicken parts separated (or if you buy your chicken pre-cut by part), know that usage is not always interchangeable. Chicken breast is white meat; all other parts have dark meat.

The neck and back of the chicken are great formaking bone broth because of the amount of bones they contain. The breast, meanwhile, which is more meat than bones, won’t make a flavorful broth.

Bone-in thighs, legs and wings are great forcooking fried chicken. Chicken filletscan be fried, steamed, broiled, poached or grilled. Fillets are especially great forstir fries.

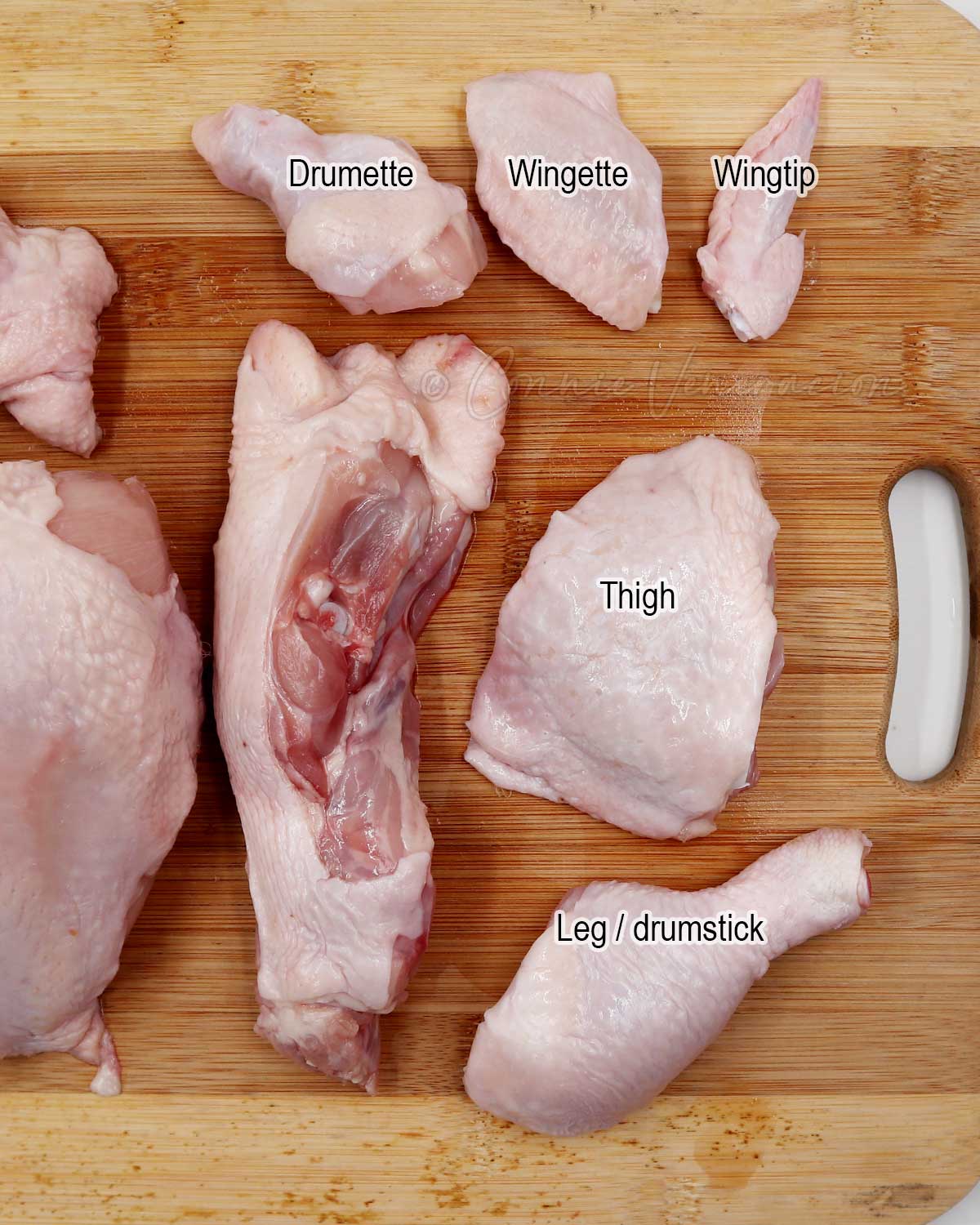

Parts of a chicken wing and leg

When a recipe calls for chicken drumette, what exactly is that? Chicken drumette is part of the wing. It looks like a small leg (drumstick). If you scrape the meat from the thin end and push it down or wrap it around the meat on the thick end, it’s sometimes called chicken lollipop.

The thigh and leg can cause confusion too. In the Philippines, the leg (drumstick) is sometimes referred to as paa (feet) which it isn’t.

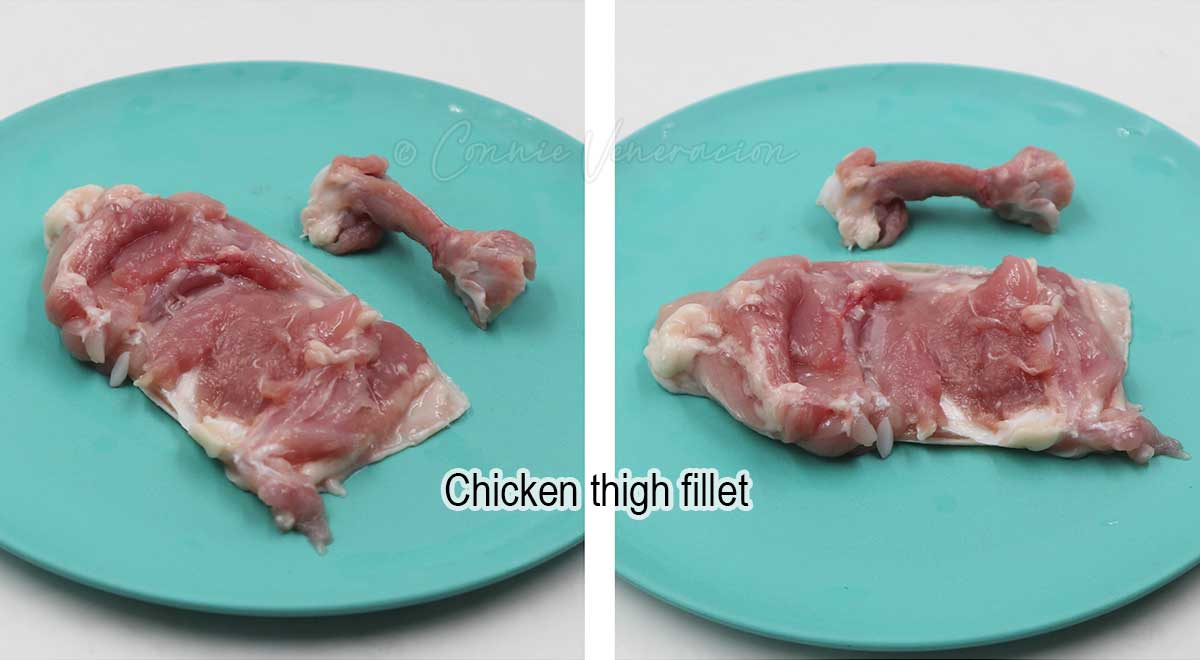

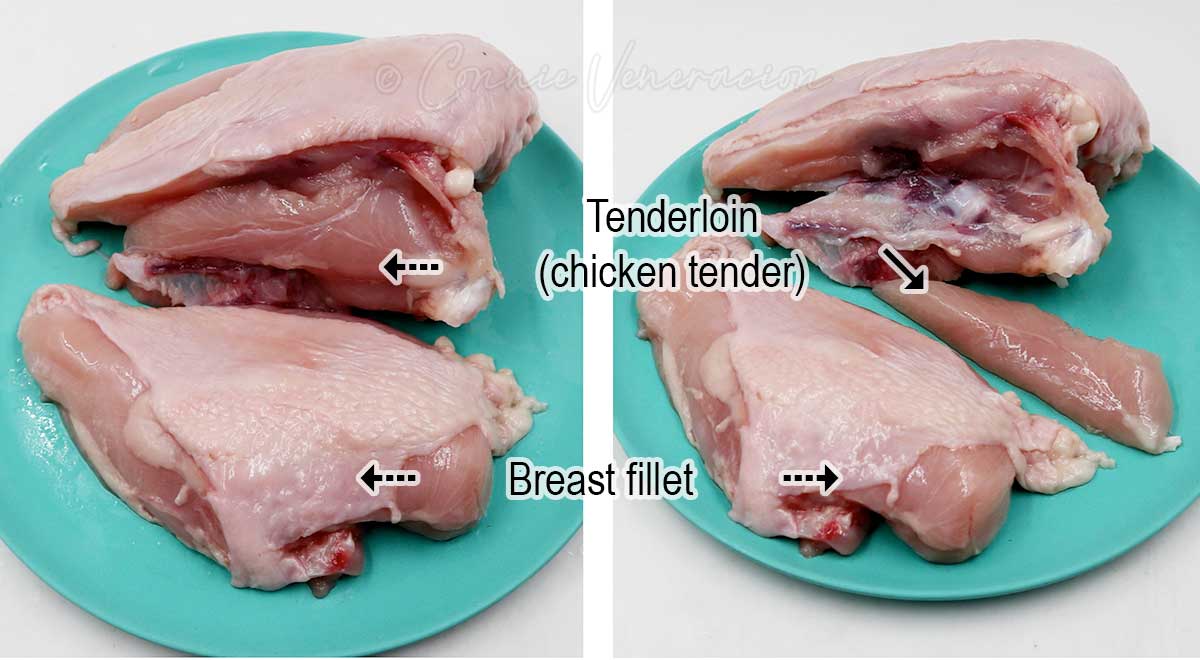

Chicken fillets

Chicken fillet often comes from the drumstick, thigh or breast and it is sold either skin-on or skinless.

The chicken breast yields two fillets: the left and right sides. When a recipe says “1 chicken breast fillet”, it usually means the fillet from half of the breast. In other words, “1 chicken breast fillet” is NOT the same as fillet from one whole chicken breast.

Chicken tenderloin (or tenders) is the strip of meat between the fillet and the bone. Just like breast fillets, you get two tenders from one chicken breast.

Chicken organ meats

There are parts of the chicken that escape “plumping”. These are the organ meats.

Chicken heads and feet

They’re discarded as unfit for human consumption in many countries but, in many part of Asia, chicken heads and feet are considered delicacies. Like chicken livers and gizzards, chicken heads and feet can be bought by weight.

What’s the difference between giblets and gizzards?

You’ve seen or heard both terms especially in relation with chicken, duck and turkey. During Thanksgiving, especially, when recipes for gravy list “giblets” or “gizzard” among the ingredients. What’s the difference between giblets and gizzards?